From The Atlantic:

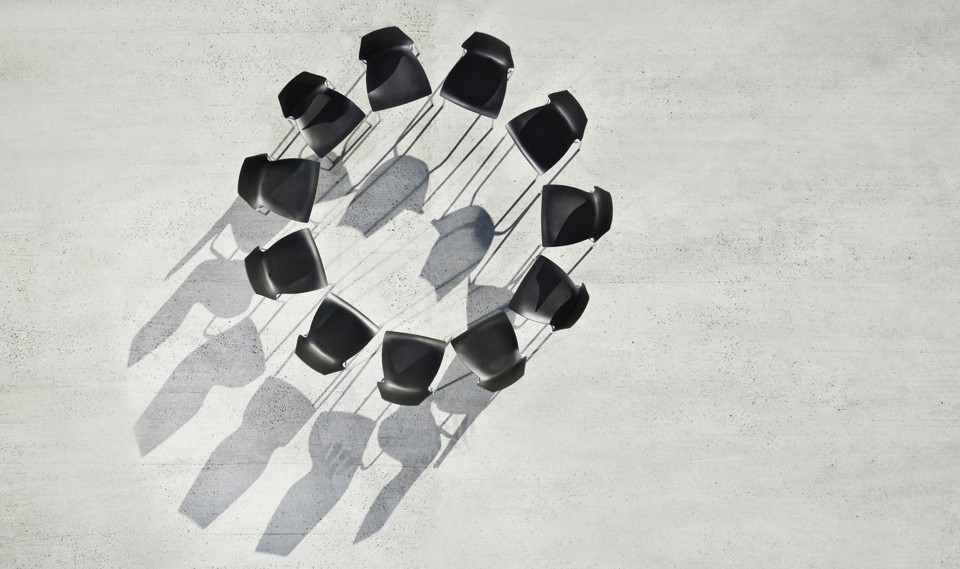

It’s a Sunday evening in Austin, Texas, in a calm gray room the perfect size and shape for a circle of around 30 adults. It’s a fairly diverse group, though there are more men than women here. Most of the guests look about 30 or younger, and a majority seem to already know each other. Right now, I know nothing else about the people I will spend the next three hours with, but I’m expecting I will soon—we are all here to “authentically relate” to one another.

We’re gathered here for a game night, a cornerstone of the authentic-relating movement, which aims to give people tools to connect more meaningfully with others. The movement, still grassroots, but growing, began in San Francisco in the late 1990s and now has a presence in 50 communities in 14 different countries throughout the world. Some of the biggest outposts are in Austin, Boulder, Montreal, and Amsterdam, and authentic-relating techniques have been taught and practiced in schools, software companies, and start-ups. Sara Ness, the movement’s unofficial organizer and the founder of Authentic Revolution, the Austin outfit, estimates that 4,000 to 5,000 people go to similar game nights each week around the world. They play games like the “Handshake” game in which partners make nonverbal eye contact to “meet” the other (without shaking hands) and “The Noticing Game,” also known as “intersubjective meditation,” in which a pair goes back and forth sharing their perception of the other’s actions and answers as anxious, argumentative, confident, or guarded and so on. The movement now has a manual, curated by Ness, of around 150 games created by facilitators the world over.

“Authentic relating” is a rather vague term. People I spoke with described it variously as a tool, a technology, and as a kind of magic or Jedi skill (jokingly). Like human relationships themselves, the practice is hard to define and easier to experience.

Authentic relating uses exercises, or games, to teach the skills necessary to quickly create deep, meaningful human connection.

But in the plainest human language with which I can explain it: Authentic relating uses exercises, or games, to teach and facilitate the skills, like curiosity and empathy, necessary to quickly create deep, meaningful human connection. In a period when loneliness is increasing as our avenues for connecting expand, practitioners tell me they are drawn to a community that makes conversing and relating with one another an intentional activity—one with guidelines and structure designed to elicit intimacy.

“On a basic level, it just gives people a place and excuse to connect with each other, which is most of what we need for wellness,” says Ness. But Ness and other enthusiasts also believe the techniques practiced in authentic-relating exercises help users develop agency and a sense of self as they begin to better relate to others.

The theme for this evening is “owning your experience” and Victor, a first-time head facilitator, longtime practitioner, quiets our casual chatter to give a speech.

“Three-and-a-half years ago I came to authentic relating and the games that I played when I first got here—I started being able to realize that my experiences are my experiences. If you ask me about my past, I’m going to tell you about my trauma, the things that are most nerve-racking, things that years ago I would not have shared with anybody. I want everybody to be able to do that, to go, ‘This is who I am. Everything that has happened to me up to this point is my experience and the reason that I am where I am and am who I am.’”

And we’re off.

Victor, Sara Ness, and one other facilitator named Stephen begin by explaining the only five rules, or “agreements,” governing what happens over the next three hours. All game nights use their own set of rules to create a “safe container” where participants can feel comfortable being vulnerable. (The Austin community recently introduced a “mandatory reporter” at some game nights, whose job is to report to legal authorities if anyone says anything that indicates they may be at risk of harming themselves or others.)

As a group, we agree to be present and focus on the here and now; to respect ourselves and abstain from any game if we feel the need to; to conversely “lean into our edge,” or embrace discomfort that we might feel in sharing; to adhere to confidentiality when requested (by default what is said at a game night may leave the room); and finally, to check our assumptions of others and their intentions. This particular evening’s confidentiality agreement came with a disclaimer that I was reporting on the event.

We warm up with a light exercise that requires us to walk the room aimlessly, pretending to be first our 10-year-old selves playing together on a playground and then our teenaged selves interacting at a school dance. In many ways, the environment feels like a youth camp: Our initial shyness during this exercise gives way to giggles that will settle into a comfort with one another as the night progresses. Everyone here seems open to the experience—it is, after all, a self-selecting group.

After we reconnect with our past selves, we pair up with a partner to share those selves. Most of the games are heavily structured; the length of the exercises and who shares what when (the tallest person or the person with shortest hair goes first, etc.) are dictated by the facilitators. For one minute, a man named Jonathan tells me how his teenage self would be surprised that he hadn’t received a Ph.D. or finished college. “15-year-old me would be surprised to see me in this group, I wasn’t as social back then,” he tells me, though he speaks now with self-assured ease. Then it’s my turn, and I stumble, nervously trying to articulate the complicated view I have of a younger me, unsure of how to externalize feelings that feel so internal. I struggle to maintain eye contact without my usual, people-pleasing song and dance as I describe how harshly I treat the 15-year-old me who wanted so desperately to be liked.

After each game, we regroup to check in with any feelings that came up while playing. “Shares” like this are a constant throughout the night. One man says he’s grateful to shed his “constantly ashamed, constantly wrong, outcast, ostracized” 10-year-old self to return to the present.

The next exercise, “Anyone Else?,” is a sort of take on “Never Have I Ever,” meant to help us find points of connection with each other. Victor chose it, he says, because the game “really set it over the edge” for him when he first started playing by helping him to realize he wasn’t alone in his experiences. To start, a man stands in the center of the circle and says, “In my teenage years, I was a loner and an outcast. Anybody else?” Everyone who relates to that statement stands up and tries to claim another seat, musical chairs style. The last person left standing then offers up their own vulnerability. “In my entire four years of college, I did not date anyone. Anybody else?” “I regret not seeing the positives about myself. Anyone else?” “In the past, I never celebrated a birthday. Anybody else?” When no one stood to relate to the birthday-question poser, a woman asked to give him a hug and a man volunteered to take his place in the center.

At one point, we split into smaller groups of five and six and use “sentence stems”—“One time in high school, I …” or “One time, when I first started dating, I …”—as a jumping-off point to share anecdotes as quickly as possible. Then, each member of the small circle is put into the “hot seat” to be questioned about their experiences for three to four minutes. This was the most thrilling exercise of the evening. With a conversation structure already in place and the normal anxieties of social interaction absent, I wasn’t asking questions to people-please or to be polite or to make small talk, and I wasn’t worried that my group members would be bored or turned off by me talking about myself. The one-directional flow of attention toward one individual allowed us to share about ourselves uninhibited by interruption or pretense.

“With attention purely on me [in the hot seat], I had the opportunity to explore deeper into myself than I would have if [my partner] had responded with things like, ‘That reminds me of a story my sister told me once,’” says Amy Silverman of the Connection Movement, an authentic-relating group in New York. “That happens in typical dialogue where we kind of ping-pong: ‘Let me tell you something about me, oh that reminds me of something about me.’”

At the Austin game night, we regroup back into one big circle, and we once again share how the exercise made us feel.

One man notes that a few people in his group bear “pretty intense” anger toward their moms.

“This is my first night and it was both more and less intimate than I expected it to be,” says another man.

“I realized I knew more about people [in my group] that I’d just met than I knew about some of my best friends,” someone else adds.

The group laughs together and Stephen, the facilitator, says “It sounds like there was some resonance in the room.” We break for gluten-free chocolate-chip cookies, chips, salsa, and tea.

Bryan Bayer, one of the original cofounders of the movement, knows just the resonance he means. After moving in his 20s to San Francisco, Bayer and a group of like-minded friends began to challenge one another to be completely honest about their feelings—anything they felt like withholding due to shame or fear had to be said—in an attempt to build intimacy. The practice was so rewarding that they began to think of how they could bring it to the world and eventually developed early games and programming.

“It just created a type of closeness that whenever we went to little parties or types of gatherings, people would be like, ‘Hey, what are you guys on? Can I have some?’ and we were like, ‘No, we’re just high off each other and raw honesty,’” says Bayer. “Just revealing something vulnerable about yourself can be its own rush, it can be its own thrill.”

The thrill—which was described to me by all involved in the practice—helped the movement spread, usually from person to person, each captivated by the joy the already initiated seemed to possess. The facilitators I spoke with all mentioned seeking out deeper connections from their personal relationships after getting involved in authentic relating. One Austin attendee named David, who was at game night for his second time, told me that finding authentic relating was like “bringing fish to water.”

At the event I attended, about three-quarters of participants were repeat guests like him. Regulars who really take to the weekly games nights can become a member of the Austin authentic-relating community. (Each individual game night is $10 without membership, and free for members.)

There are, of course, plenty of ways to meet people and join a community that don’t involve sitting in a “hot seat” while people pepper you with personal questions. Some of those means, though, are on the decline—religion, and even traditional office spaces, for example. But initiates of authentic relating paint a picture of a meaningful, exhilarating connection that’s more difficult to find in the day-to-day.

“For me, the only thing that heals someone is a relationship,” said Sean Grover, a psychotherapist who runs one of the largest group-therapy practices in the country out of New York. “Lack of attunement between people now is the norm. Technologies, cellphones, people are just so out of tune with each other.”

Social media is an obvious and oft-cited culprit. Peter Benjamin, a life coach who helped build the authentic-relating-games community in Boston, thinks that many people have started to fill holes in their lives with technology instead of relationships.

“Ostensibly we’re supposed to go from depending on our parents for support in moments of confusion. A lot of people, instead of transitioning that to their friends and community, it gets transitioned onto technology, and so in times of stress, [feeling] overwhelmed, challenged—where do they go? They go to Netflix or social media, YouTube, whatever,” says Benjamin. “We tend to defer our pain and numb it rather than really facing it. It seems to be filling in a gap.”

No one I spoke to from the authentic-relating movement sold it as a therapy equivalent, but some people have found that these game nights help improve their mood and alleviate anxiety. I certainly felt the game-night high afterward. Jonathan, my partner from earlier in the evening, told me that authentic relating was the only thing that helped stabilize his depression. Sara Ness said that authentic relating improved her confidence after a teenage-hood as a lonely “awkward geek” who hadn’t yet learned social skills.

Grover had no qualms about the authentic-relating movement, though he did warn that not having a trained person on hand to handle any difficult emotions that may come up could be potentially dangerous. He says he does, however, see similarities between the exercises he uses and the techniques deployed in authentic relating. As is, three of the Austin community’s five rules—being present, leaning into your edge, and respecting confidentiality—Grover also uses in his group-therapy practice.

In the process of reporting this story, my psychiatrist suggested I try group therapy to help me recognize I’m not alone in the anxiety career uncertainty brings. When I described authentic relating, she said the practice sounded helpful, and that it might be comforting to interact with a more diverse set of people—as opposed to a more homogeneous group of similar age range, as is often gathered for group therapy—who had made it past this life stage, the 20s. I thought of Jonathan, who hadn’t finished college or received the Ph.D. his younger self expected, but seemed at peace.

Ultimately, Ness said, the goal of the authentic-relating movement is “trying to spiderweb into all new areas” so that one day it might “be the norm to communicate this way.”

Early in the evening, Ness encouraged us to pause. “Take a moment to just actually look at each other, make eye contact, acknowledge that you’ve shared what could be some pretty vulnerable stuff and you’re witnessing each other’s humanity, in a way that maybe we don’t often get to share,” she said. “With your eyes, just let this person know that you see them and that you have a version of them too.”

The very last game of the night is all about sharing these versions of each other that we contain. We split into two large circles. We once again summon younger versions of ourselves. By this point in the evening, I feel completely at ease with the people around me. I’m honestly surprised there’s no voice in the back of my head questioning the hippie-dippie, touchy-feely nature of the exercise. Perhaps I’m genuinely in the moment, suspending assumptions about myself and this exercise. We’re instructed to think of something our younger self really needed to hear in the past, but didn’t. Then we go around the circling, saying that something to the person to our left. We speak to regret, shame, and healing, telling the people in our group and telling ourselves too.